The 10th Indonesia EBTKE ConEx 2021, a forum on new renewable energy and energy conservation for an energy transition towards zero-emission, took place from 22 to 27 November 2021 virtually. The platform invited visitors to enjoy a variety of virtual activities, including conferences, training, exhibitions, field trips, career fairs, business presentations, and business matching. The MENTARI programme fully supported this event.

MENTARI is a collaboration between the Indonesian government and the British government through the British Embassy in Jakarta to support the transition to low-carbon energy and promote inclusive economic growth. MENTARI was involved in various activities during Indo EBTKE ConEx 2021, including a jointly-facilitated discussion entitled: ‘Mini-grid talk: How do we monetise mini-grids in Indonesia?’ This took place using the Zoom platform on 23 November 2021.

Chrisnawan Anditya, director of variable new and renewable energy, Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, and Julio Retana, MENTARI’s team leader, jointly presented the event. The speakers included: Surgadiana Pamungkas from TMLEnergy, Amelia Buddhiman from Akuo Energy, and Fajar Sastrowijoyo from Syntex Energy & Control. Other participants included: Didit Waskito from the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources; Daniel Tampubolon from PLN in East Nusa Tenggara; and Pariphan Uawithya from the Rockefeller Foundation. Fabby Tumiwa, a director of IESR, moderated the discussion.

Chrisnawan launched the discussion by recognising the value of off-grid renewable energy, particularly in providing electricity for people living in remote areas. The private sector and PLN, as the state electricity company, need to get involved in off-grid renewable energy plants and services. Meanwhile, these services can be managed by village-owned enterprises or local cooperatives to ensure they are sustainable. Local governments must also develop human resources with the skills to design, build and manage these renewable energy projects and the new technologies they require.

Julio Retana agreed, but he stressed that, “The system is not only about equipment and cables and batteries, but it also creates a paradigm shift in the community.”

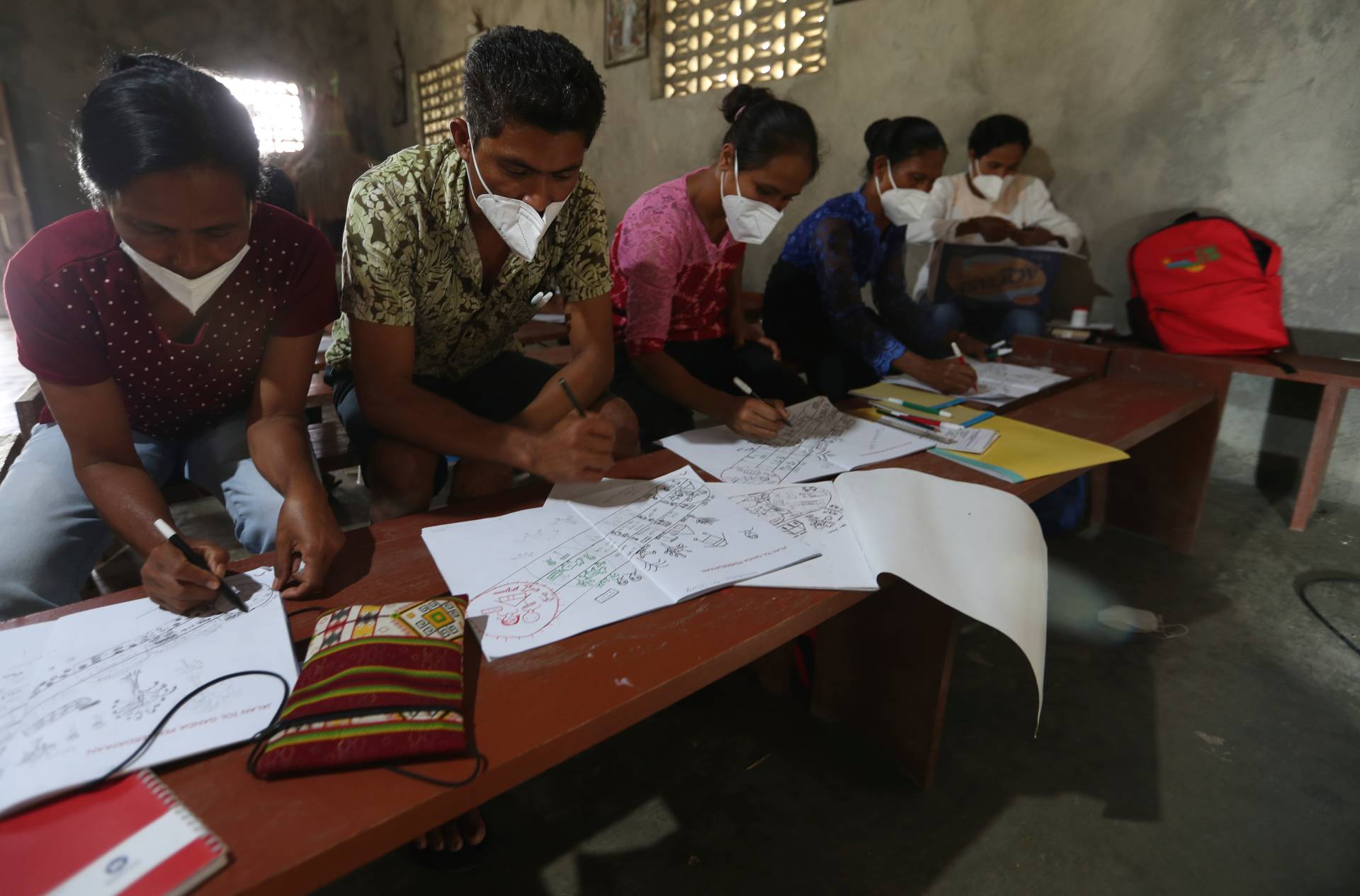

Julio explained that the goal is for communities to own, manage and operate the solar power plants (photovoltaic systems) and be self-sufficient once the initial project ends. Therefore, as the plant is being developed, MENTARI also builds the infrastructure for the enterprise that will manage it, starting by providing technical training. The plan is that the villagers will go on to install proper electricity systems in their own homes.

The discussion turned to the logistical aspects of procuring the main components for the solar power plants, particularly for the mini-grids. The speakers went on to recount their experiences of developing mini-grid projects in various remote areas in Indonesia. They spoke about issues in operating and managing such systems, particularly the challenges of a sometimes intermittent and unstable energy supply. This led to a lively exchange between participants and speakers, especially on involving local governments in the transfer of knowledge and using village-owned enterprises to run the plants.

Pariphan Uawithya shared his experience overseeing various mini-grid development projects in different countries. He stressed three key issues in a successful mini-grid project. Firstly, the developers should be allowed to distribute and sell the electricity to consumers at a price agreed by the community and the company. Secondly, the sales and service for the project needed to be competitive. The project will be sustainable if the mini-grid can sell electricity at lower rates than consumers would pay for diesel engines or other alternatives. Services the grid provides must also be reliable – and even better than on-grid electricity.

The third key issue in monetising mini-grid systems and making them sustainable is how much electricity people use. Installing a mini-grid is not only about bringing energy to the community but also about spurring energy consumption to reach 1000 kWh per capita – the minimum consumption for a viable service. This means encouraging productive use of power. In the programme Pariphan carried out, they created a cycle that not only made the mini-grid project worth financing but also increased incomes for the village community.

Around 2,200 to 2,500 villages in Indonesia do not have access to electricity, according to 2019 data from the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources and the Ministry of Villages, Development of Underdeveloped Regions and Transmigration. Energy access has improved, and the electrification ratio currently stands at 99 per cent.

Nevertheless, as a populous country, a significant number of people still have no electricity. The conventional electrification programme is insufficient to electrify the remaining villages and would require large investments. This is an opportunity to use the off-grid system and mini-grids to expand access to electricity – specifically electricity from renewable energy.

Creating an electricity demand is key to promoting inclusive economic growth and alleviating poverty. Mini-grid systems can be complex and must be well managed, especially for human resources and institutions. We need to standardise the systems we use and develop sufficient capacity to operate and sustain the mini-grids in terms of technical maintenance and human resources.